Re-wilding My Digital Art Process

On becoming less dependent on digital tools and returning to a more human, joyful process.

I am constantly thinking about my illustration style. I’m obsessed these days with returning to a more analogue-based process. This latest obsession began over a year ago when I was encountering serious style fatigue (this pervasive, overwhelming loss of interest in my own illustration style). At first, it was a sort of background ennui that I tried to ignore, knowing how hard I’d worked over the years for a consistent, recognizable style. (The whole point of having a style for me was to have the most possible confidence throughout each illustration project, both artistically and strategically speaking). But this background ennui grew into an almost depressive state that was impossible to ignore. In a moment of clarity, I realized what the root problem was: it wasn’t that I hated my style so much as I had grown bored with the process.

Update: 4 June 2025 — I ended up recording this essay as part of a podcast episode. Here it is for your listening pleasure.

To keep this story short, I’ll just say that there was a time, in my beginning stages as an illustrator, when I prided myself as an “inky” illustrator — making most of my textures, marks and line-work with real, physical media, and working with a mouse rather than using digital brushes or a stylus. This more constrained technique naturally and profoundly shaped my style, making it more logical to work with chunkier shapes and piece everything together in a collage-like way. As nice as the digital brushes on my machine were, it was basically impossible to use a mouse to control them. But then, as I got busier, I leaned more into digital tools — namely my iPad and Apple Pencil — which made me way more efficient. Through these tools, I became less true to my “inky” way of working. Having more pen-like control with the Apple Pencil, I was finally willing to give digital brushes a try. I did my best to always include a few analogue-made elements, especially whimsical textures and hand lettering, but within a couple of years, I had grown confident enough with using a purely digital toolkit for my illustrations, from start to finish. Without the natural constraints of working with physically-made elements and a mouse, my shapes became less chunky, my compositions less collage-like, and my images became far more precise and controlled. I even expanded my colour palettes from maybe 3-4 in a given piece to up to 10 or more. By the time I hit peak style fatigue, there was almost nothing left of my original style.

I am not anti-digital, but I’m fed up with the expansive nature of my tools, and how they confound me with complexities and options that I have to wade through, which sometimes get me stuck in indecision loops — and worse, bloat my illustration process.

Now, about this idea of “re-wilding” my process — I’ve heard this term used over the years in the context of gardening and landscaping. The idea here is to let nature run its course and be more hands-off about what grows where — all in service of restoring natural ecosystems and biodiversity. I’ve also heard the term used informally to refer to other realms, such writing and even spirituality. I suppose the idea is to stop trying to control everything so much. To step aside and make a way for the natural good to grow and do things that couldn’t be possible with more left-brained interference. Another, similar term is “re-enchantment”, in which people are going back to seeing the world as a more magical, spiritual place. This seems to be an unravelling of all the rigid, systematic, scientific thinking we in the modern West have been steeped in for so long. I mention this only to place ourselves in this specific moment, where people seem to be pushing back against the digitalization of everything — including our creative tools. Many of us are longing to go back to a hands-on (and hands-dirty) way of creativity, not simply as a stylistic choice but as a reclamation of what it means to be human. This is especially in reaction to AI’s not-so-secret mission of taking over pretty much every kind of work — whether meaningful or menial — we humans once thought uniquely, and safely, ours.

For me, re-wilding means de-digitizing my process. I wouldn’t completely un-digitize it, any more than I would stop using a computer as my main writing tool, but I am looking for ways to take back the key parts of the process that I believe digital has taken from me — and to bring them back into physical materials and space. Perhaps another way of saying this is that I want to re-incarnate my illustration process. In the same way that technology seems to be pushing all of society towards total disembodiment, my over-digitalized creative process, it seems, become disembodied. I want to give it a body once again.

I am looking for ways to take back the key parts of the process that I believe digital has taken from me — and to bring them back into physical materials and space.

So right now, I’m simply asking how I can bring more analogue techniques back into my process. Particularly, what are some interesting ways of replacing digital tools and techniques?

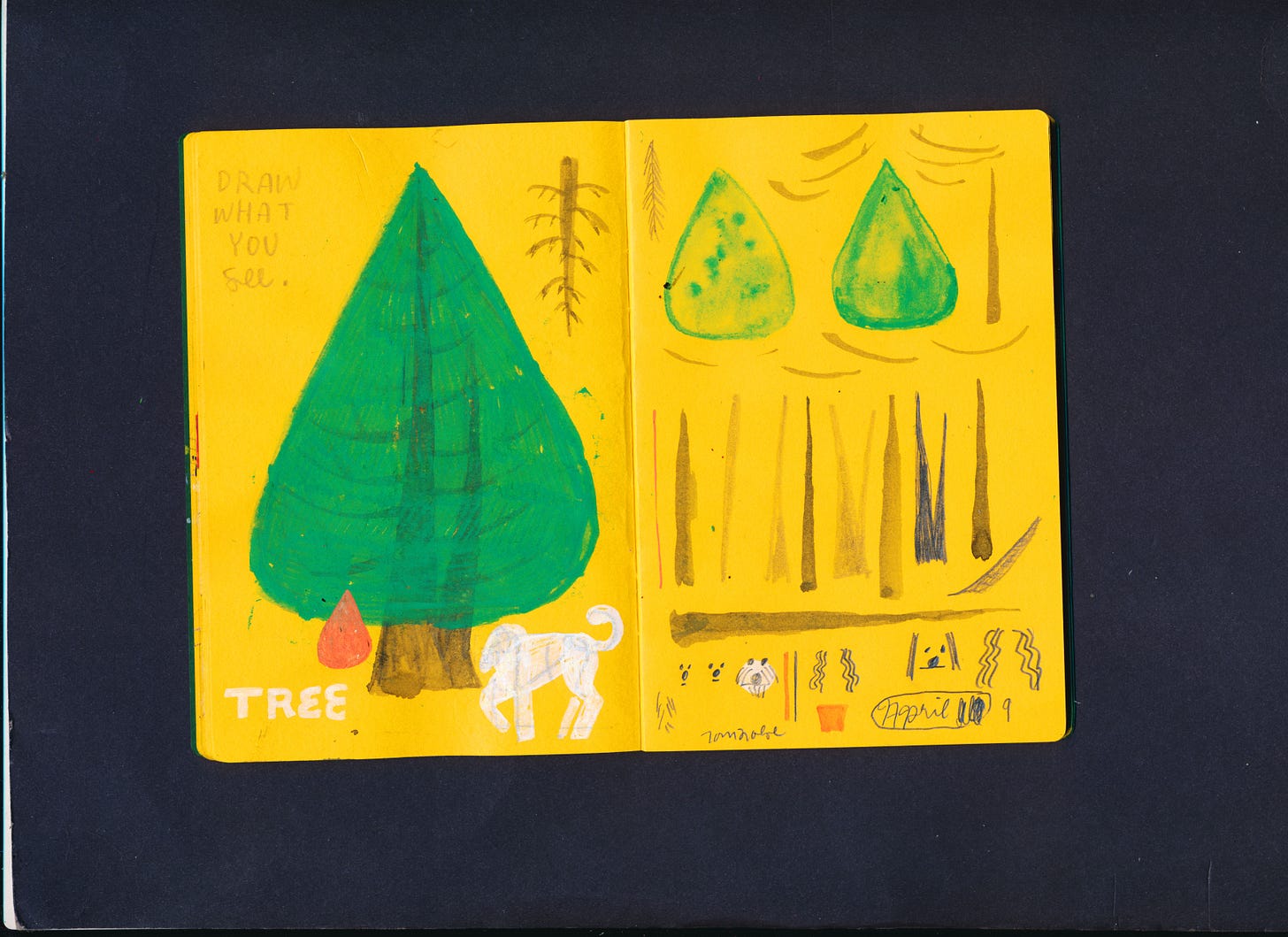

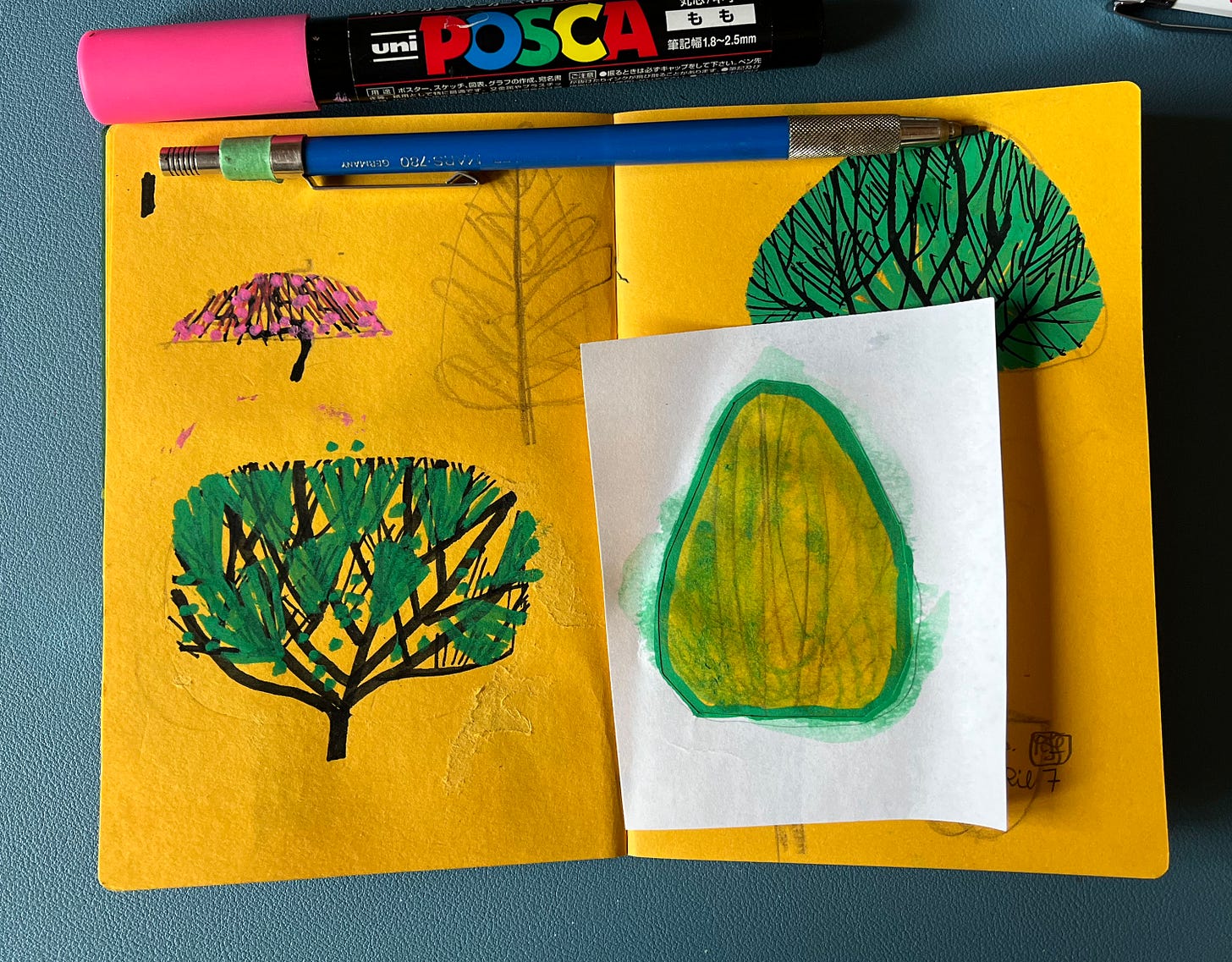

This week, I’ve been inspired to draw trees as part of my daily drawing practice. I’ve been using this as an opportunity to explore techniques that I could bring to my professional illustration process. How can I create lines, shapes, marks, and textures using only physical media — and what techniques can I use to control them in similar ways to how I work digitally? For example, in Photoshop, I use vector masks to create crisp, cut-out shapes that contain various colours and textures. In real life, I can draw colours and textures on paper and cut them out using a scissors. Or I can make a template (or “frisket”) and use that as a mask, thus letting marks drawn within it come to a clean, well-defined edge.

You might wonder why I would prefer this much more roundabout process when I could do it way faster in digital? And this really gets at the whole point of re-wilding for me — the process is harder to control, it’s more limited, and it creates more unexpected results. It’s in this space of having an idea to follow, without a guarantee that the results will be exactly as I expect, that makes the whole creative process interesting to me, and I believe this results in images that are more interesting to others.

Now, don’t get me wrong: I owe my entire creative career to digital tools. Without Photoshop, I would not have been able to make my earliest illustrations, and I have never been very good at controlling my work in purely analogue situations. I am not anti-digital, but I’m fed up with the expansive nature of my tools, and how they confound me with complexities and options that I have to wade through, which sometimes get me stuck in indecision loops — and worse, bloat my illustration process. Once you have a digital illustration app like Photoshop or Procreate, you have an infinite supply of paint in every colour imaginable; you have a dizzying array of tools and brushes that will never wear down or get lost. Expensive art paper is a thing of the past. In the purely digital realm, everything is possible — and this is not necessarily a good thing. There are no conceptual constraints, no budgetary constraints, and no physical constraints — and constraints are exactly what we need in order to be creative. Your style is the result of how you creatively work around certain obstacles. Devoid of natural constraints, every option in a digital environment becomes a paralyzing moment — at least for this decision-impaired artist.

Whereas in the physical world every tool has its natural property, which creates an inherently unique mark or effect, in the digital world, I have to consciously apply certain tools and settings to create a desired result. While this is true of physical media, it’s pronounced in digital, where I have to create artificial limits around what my style does and doesn’t “do”, lest I use completely incongruous features that crash together in a visual cacophony. Any colour is possible. Any brush type is possible. Any edge quality is possible. Whatever you want, there’s probably a tool, brush, or effect for it. The incongruity comes from how disembodied any of these effects is from the real-world media they were programmed to imitate.

On the other hand, where digital tools provide a unique opportunity that analogue tools can’t, or can’t do very well, then that is where they truly shine. Clean backgrounds, crisp shapes, and perfectly uniform and solid colours are all best done in a digital tool like Photoshop. But it’s these very things that I’ve worked hard to overcome in my digital process, looking for the most natural looking pencil brush or edge quality to bring into my work without having to leave my computer. It turns out that the best way to get natural-looking elements and analogue-like spontaneity is by using natural, analogue tools and techniques. It’s so obvious, but that I had to say it does speak to this strange world we find ourselves in today — we construct elaborate, complicated machines to do simple tasks. All the technology we use today, we were promised, was supposed to make our lives easier, and we all know how that story goes.

… as I got busier as an illustrator, I leaned more into digital tools that made me more efficient, as well as more predictable “moves” in my illustrations themselves that were easy enough to hammer out without too much turmoil. By the time I hit peak style fatigue, there was almost nothing left of my original style, which was in almost every way dependent on the strong analogue-digital process I had developed.

Meanwhile, we’re all trying to find more balance in our lives. We want to get off our screens. We want to jump off the digital hamster wheels we’ve built for ourselves. The question here is, what is stopping us from just doing it?

Of course, in my case, it’s my legacy. I have built a career around the work I’m doing now, and I don’t think it’s wise to simply detach myself from who I am today to pursue a possible (but not guaranteed) better version of myself tomorrow. Like everything, my quest to decrease the presence of digital tools in my process and the overly-digital “look” in my work must be an evolution — a quiet revolution. The early grumblings of this quiet revolution have been going on for some time. The only way they can grow and thrive, without a total shock to my own practice, or to my various audiences and clients, is to set apart areas in my work where they are allowed to grow free.

I wouldn’t recommend anyone completely re-wild a society, nor would I want to live in a totally re-wilded house (I can live without black mold and rodent feces). But we can cooperate with nature in ways that give the best of it a chance to show up, by setting aside spaces where they may do so. I’m looking for a more broad re-wilding of my illustration process, that I hope one day replaces the purely digital ones that have overstepped and overstayed their welcome. On the way to that glorious time, I’m happy to work it out in smaller areas of my practice, especially in my daily drawing practice (as, of course, trying out new things is exactly what side-practices are for!).

Whether I can use a totally re-wilded process in all my client work I just don’t know. But I’ll never know unless I work at it consistently, and risk giving it a chance in more significant ways from time to time. My goal is to be liberated from the over-plentitude of options and controls of digital, and to let the inherent, natural constraints of analogue techniques take over more. My goal is also to become less dependent on increasingly expensive hardware and software. And of course, all of this is in service to making work that not only feels more human and wild to create — it also calls out to something more human and wild in the eyes of those who behold it.

—

p.s. It’s one thing to explore a technique or style, but another to figure out what to do with it. How will it work in practice? What uses or contexts will it be most suited to? What will its biggest limitations be? In my move to a more analogue style, I’m also moving to specific ways that it can be used or not used — and being a more time-staking process, how much work I can take on at any given time. Questions of efficiency usually lead to questions of profitability. I’ll have to explore this in a future post.

Rewinding your illustration sounds like a fun class idea!

I love this!! I’ve been going through a similar process. I’m curious what physical tools you’ve returned to and if you have any recommendations- I love the vibrancy in your sketchbook pages!